Reposted with permission from Georgetown University and CSET. Click here to read the original article.

Written by Hanna Dohmen and Jacob Feldgoise | Originally Posted December 4, 2023

On October 17, 2023, the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) issued an update to last year’s export controls on advanced computing, supercomputing and semiconductor manufacturing equipment. This blog post provides an overview of the updated advanced computing controls, analyzes more than 100 relevant chips, and discusses the licensing policies for the expanded chip restrictions and the increased country scope.

On October 17, 2023, the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) at the U.S. Department of Commerce issued highly complex and extensive updates to the October 7, 2022, export controls restricting U.S. exports of advanced chips and semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SME). These export control updates are intended to stay up-to-date with technological developments of AI systems and manufacturing of advanced chips, as well as address gaps in the October 7, 2022, controls that became apparent over the last year.

These latest controls are designed to more effectively advance the Biden administration’s stated objectives of blunting China’s military modernization and maintaining U.S. military leadership. More specifically, the aim of the controls is to limit China’s ability to use large-scale AI systems to develop weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and advanced conventional weapons by restricting access to the advanced chips needed to train frontier AI models and the SME necessary for the production of these chips. According to BIS, the agency is specifically concerned about chips that can be used to “train frontier AI models that have the most significant potential for advanced warfare applications, including unmanned intelligent combat systems, enhanced battlefield situational awareness and decision making, multidomain operations, automatic target recognition, autopiloting, missile fusion, precise guidance for hypersonic platforms, and cyber attacks.” With these updates, BIS expects that a “bigger yard” and a “higher fence”—controlling more chips and to more destinations—will be able to achieve these objectives more effectively.

In this blog post, we aim to provide an overview of the updated export controls on advanced computing.1 First, we address which chips are controlled by analyzing over 100 relevant chips. Then, we address which destinations are controlled for these chips. Lastly, we discuss an important and new “red flag” guidance and how this may affect foundries making chips for Chinese semiconductor companies.

A Bigger Yard: More Chips Restricted

To comply with the October 7, 2022, controls while still selling advanced chips to the Chinese market, chip designers, including Nvidia, legally developed chips below the control thresholds. BIS believes that such chips could “provide nearly comparable AI model training capability,” so the agency revamped the criteria used to determine which chips are restricted. Notably, BIS removed the interconnect speed parameter (the rate at which chips talk to each other)—the same parameter around which Nvidia had designed its China-specific chips. With the October 17, 2023, controls, BIS now identifies controlled chips using three criteria: the chip’s total performance, performance density, and whether the chip is “designed or marketed” for use in a datacenter. Under this updated system, a lot more chips are controlled, including high-performing gaming chips and lower-performing datacenter chips—not just those chips needed to train frontier AI models. Whether a controlled chip ultimately requires a license to be exported depends on its destination (see the “When Do Chip Controls Apply?” section for more details).

Total Processing Performance (TPP) measures the number of operations a chip can perform per second.2 U.S. government officials may have worried that Chinese companies could still use lower-performing chips—each failing to trigger the original TPP threshold of 4,800—in greater quantities to train large AI models. Officials likely sought to reduce the TPP threshold to 1,600 in order to control lower-performing datacenter chips, but, on its own, this control would be too broad; it would capture discontinued datacenter chips and consumer gaming chips, neither of which the government sought to control. To lower the TPP threshold without capturing unwanted chips, BIS introduced two additional criteria: performance density and the intended use of the chip.

Performance Density (PD) measures a chip’s compute power per area.3 It essentially serves as a proxy for how advanced a chip is. In general, chips that utilize more sophisticated designs and manufacturing processes are able to perform more operations per second within a smaller area—usually improving their energy efficiency and reducing the cost to train large AI models. PD helps distinguish between newer, more efficient chips and older, less-efficient ones.

The Datacenter Criterion distinguishes between chips “designed or marketed for use in datacenters” and those that are not (e.g., chips designed exclusively for gaming). Non-datacenter chips are only controlled when they meet higher performance thresholds (TPP >= 4800), and, even then, the controls are lighter. BIS uses this criterion to avoid controlling advanced chips that could not be easily used in datacenters to train large-scale AI systems. To evaluate whether a chip meets this criterion, BIS and compliance attorneys will consider whether the chip designer:

- Incorporated datacenter-specific features (e.g., a high bandwidth connection socket), or

- Markets the chip for use in datacenters in public-facing materials (e.g., press release or datasheet).

Companies cannot avoid licensing requirements by combining multiple less-powerful chips on a single circuit board. TPP and PD should be calculated at the highest level of integration, up to and including a circuit board. A manufacturer could not get around the licensing requirement, for example, by packaging together multiple chiplets that individually fall below the control threshold or by placing multiple, separately-packaged chips on the same circuit board; so long as the aggregate parameters of the circuit board exceed their relevant thresholds, the device would be controlled.4 The controls have treated chiplet architectures and circuit boards with multiple chips this way since the original October 7, 2022, rule.

Based on these criteria, there are three potential licensing determinations: 1) regular license required, 2) license exception eligible, and 3) not controlled. In addition to a regular licensing requirement for the most advanced datacenter chips, BIS created a license exception—”Notified Advanced Computing” (NAC)—for non-datacenter chips and certain less-advanced datacenter chips. Depending on which country and which type of entity the NAC-eligible chip is being exported to, the export may require an expedited license or no license at all (see the “When Do Chip Controls Apply?” section for more details).5

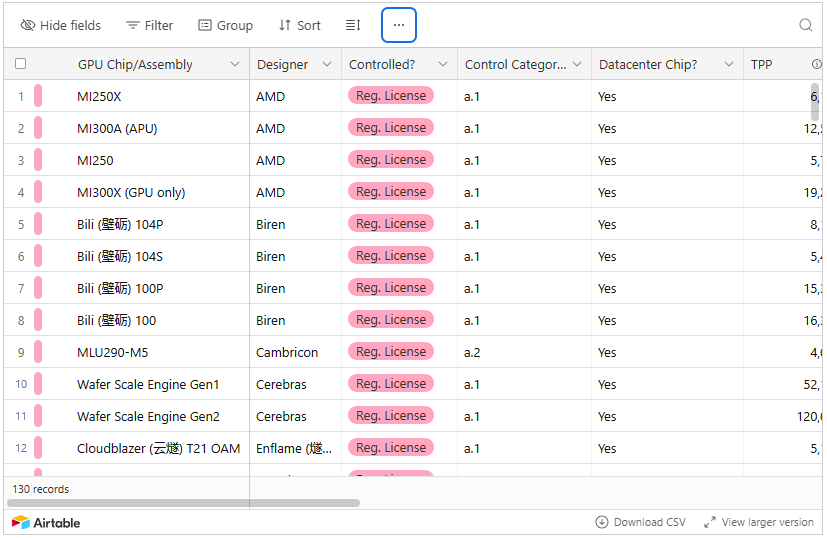

Below we illustrate how the three criteria work in tandem.

Figure 1. License Requirements Based on TPP and PD Parameters

Datacenter Chips

As shown in Figure 1, datacenter chips whose technical parameters (TPP and PD) place them in the red-shaded area, will require a regular license for export to certain countries.6 Datacenter chips that fall in the yellow-shaded area are NAC-eligible, which means that, depending on where they are being exported, they may require an expedited license or no license at all.7 Datacenter chips that don’t meet the technical parameters are not controlled and can be exported freely, as shown in the green-shaded area.8

Non-Datacenter Chips

Non-datacenter chips never require a regular license. The most advanced non-datacenter chips are NAC-eligible, as shown in the yellow-shaded area.9 Less advanced non-datacenter chips are not controlled and can be exported freely (given no other export restrictions apply), as shown in the green-shaded area.

Which Chips Are Controlled?

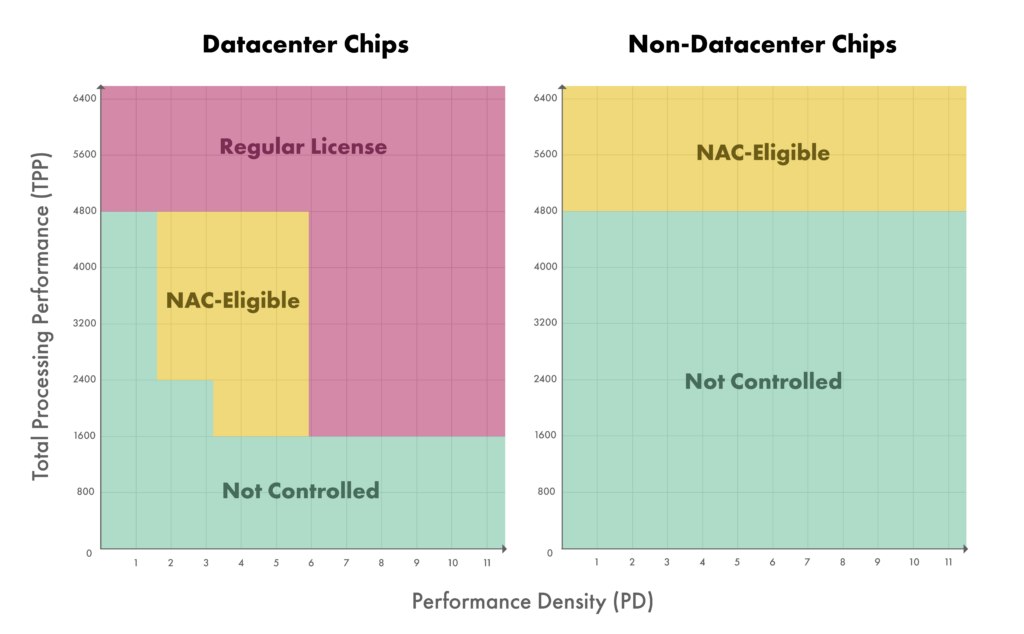

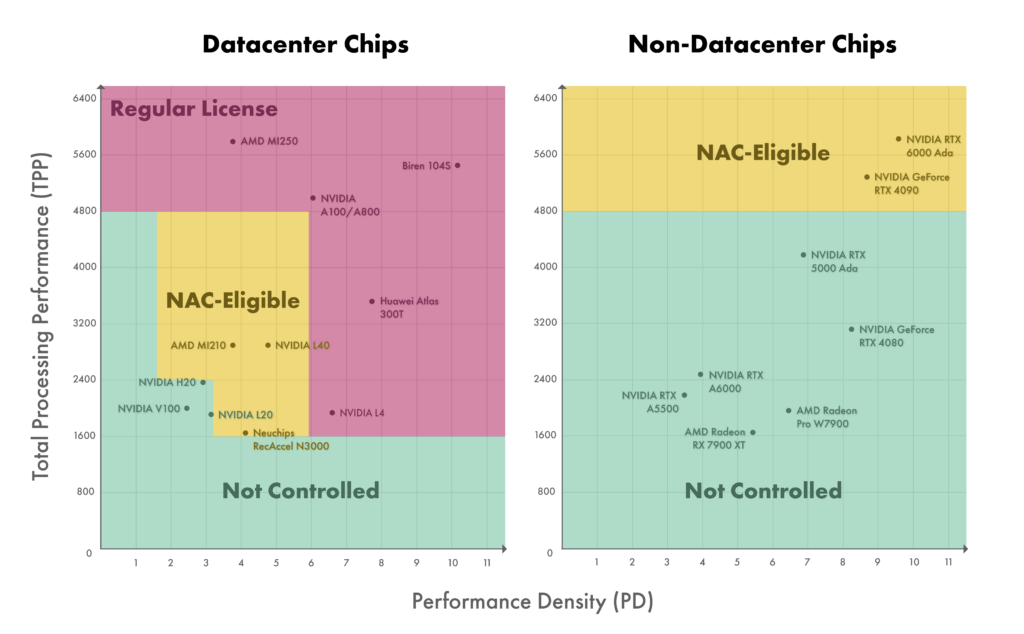

We analyzed more than 100 relevant chips to determine whether they are controlled. In the interactive table below, we provide a snapshot of our analysis.

Please note that this table is not a compliance tool. We’ve done our best due diligence to validate the three criteria for each product in this spreadsheet using the linked sources in the table below. Companies and third-party sellers of these chips should seek out legal advice to help formally determine which licensing policies apply to their products. If you have questions or would like to suggest ways to improve the table, please contact us at cset@georgetown.edu.

Table 1. Select List of Chips and Licensing Policies

Note: In some cases we were not able to find the die area, which means we were not able to calculate the performance density for those chips.

Below we illustrate license requirements for a sampling of datacenter and non-datacenter chips based on their TPP and PD.

Figure 2. License Requirements Based on TPP and PD for Datacenter and Non-Datacenter Chips

A Higher Fence: Expanded Geographic Scope

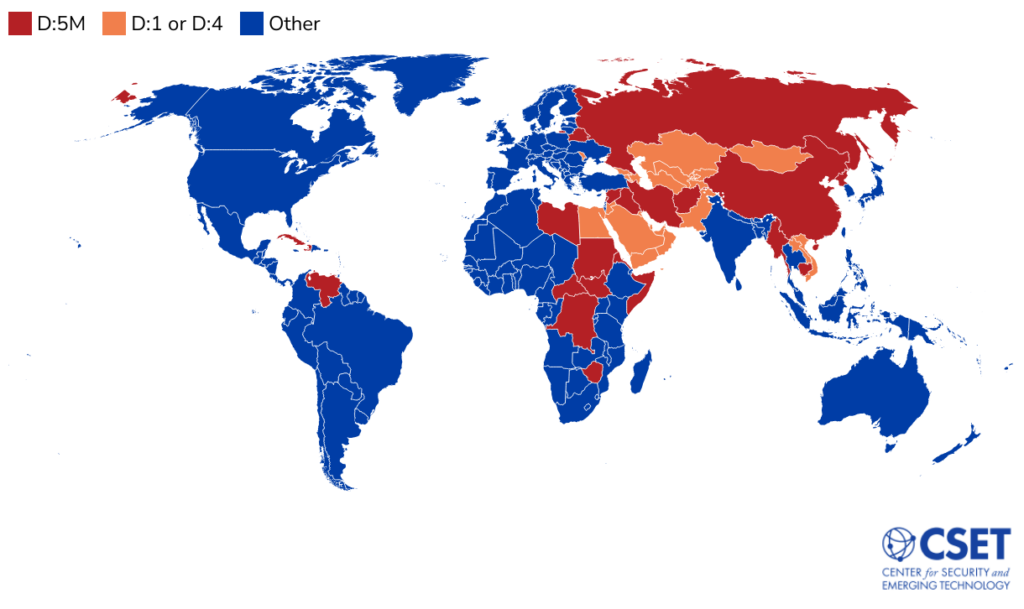

The October 17, 2023, rules greatly increased the geographic scope of the chip controls to cover additional countries as well as some corporate subsidiaries located anywhere in the world. By increasing the geographic scope of the controls, BIS appears to limit the reach of Chinese multinational companies and mitigate the risk of diversion of controlled chips through third countries. BIS is particularly concerned about those countries with “AI commercial and research ties” to China. Among the additional 43 countries to which chip controls are now expanded, Chinese researchers co-author AI papers most often with colleagues in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Vietnam, according to CSET’s Emerging Technology Observatory.

Country-Wide Controls

The October 7, 2022, controls only restricted chip exports to China and Macau; the new rules expand chip controls to an additional 43 countries, most of which are in the Middle East, Africa, and Central Asia (see Figure 3). The October 17, 2023, restrictions also expanded the existing Advanced Computing Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR) to control foreign-produced chips made with U.S. equipment when they are exported to the new set of 44 countries and Macau.

BIS determines which countries are subject to which restrictions by categorizing them into Country Groups. Country Group D:5 and Macau (abbreviated here as “D:5M”) refers to Macau and U.S.-arms-embargoed countries, including Russia, Iran, and China. Country Groups D:1 and D:4, respectively, identify countries controlled for national security reasons or missile technology concerns. Country Groups A:5 and A:6 are countries with which the United States has friendly ties.

In general, the update controls chip exports to the 44 countries and Macau included in D:1, D:4, and D:5M (excluding Israel and Cyprus).10 See the “When Do Chip Controls Apply?” section for a detailed description of which chips are controlled to which countries.

New Global Control on Entities Headquartered in U.S.-Arms-Embargoed Countries

To address the concern that Chinese companies—or other companies headquartered in U.S.-arms-embargoed countries—may use their foreign subsidiaries to purchase and access controlled chips, BIS has imposed controls on those entities. Notably, this is the first time that BIS has employed a control using an end-user’s headquarters to address circumvention risks. BIS states:

“This additional end-use control is needed to ensure that the national security objectives of the October 7 IFR and this AC/S IFR are not undermined by Macau, PRC or other Country Group D:5 entities setting up cloud or data servers in other countries to allow these headquartered companies of concern to continue to train their AI models in ways that would be contrary to U.S. national security interests.”

Controlled chips now require a license to any destination outside of the 44 countries and Macau if the exporter has knowledge that an entity headquartered in (or whose ultimate parent is headquartered in) Macau or a U.S.-arms-embargoed country, including China (“D:5M-headquartered entity”) is party to the transaction. For example, the D:5M-headquartered entity may be a “purchaser,” “intermediate consignee,” “ultimate consignee,” or “end-user.”

When Do Chip Controls Apply?

Figure 3. Map of BIS Country Groupings

Whether exporting an advanced chip requires a license not only depends on whether the chip meets the technical criteria discussed above, but also on the destination country and entity.

- Exports, reexports, and transfers of regular license chips to any entity in a U.S.-arms-embargoed country or Macau (D:5M) require a full license, which will be denied in most cases. Example: a license application for exporting an Nvidia H100 to China will likely be denied.

- Exports, reexports, and transfers of regular license chips to any entity in a country controlled for national security reasons or missile technology concerns (D:1 and D:4, respectively) require a full license. If the item is being exported to a D:5M-headquartered entity11 then the license will be denied in most cases. Otherwise, the license will be approved in most cases. Examples: 1) a license application for exporting an Nvidia H100 to an Alibaba subsidiary in Saudi Arabia will likely be denied; and 2) a license application for exporting an Nvidia H100 to an OVHcloud (French) subsidiary in Saudi Arabia will likely be approved.

- Exports, reexports, and transfers of regular license chips to a non-D:1, non-D:4, and non-D:5 country require a full license only in cases where a D:5M-headquartered entity is party to the transaction.12 These licenses will be reviewed on a case-by-case basis. Example: a license application for exporting an Nvidia H100 to a Tencent subsidiary in Germany will likely be reviewed on a case-by-case basis.

- Exports and reexports of NAC-eligible chips to any entity in a U.S.-arms-embargoed country or Macau (D:5M) require an expedited license, for which the license review standard is unknown. Example: an Nvidia RTX 4090 gaming chip being exported to China requires an expedited license.

- Exports, reexports, and transfers of NAC-eligible chips to any entity (including D:5M-headquartered entities) in a country controlled for national security reasons or missile technology concerns (D:1 and D:4, respectively) do not require a license. Example: an Nvidia RTX 4090 gaming chip being exported to a Baidu subsidiary in Vietnam would not require a license.

- Exports, reexports, and transfers of NAC-eligible chips to any entity (including D:5M-headquartered entities) in a non-D:1, non-D:4, and non-D:5 country do not require a license. Example: an Nvidia RTX 4090 gaming chip being exported to a ByteDance subsidiary in the United Kingdom would not require a license.

Table 2. License Requirements for Chips Based on Destination Country and Entity13

Note: License review standards in parentheses.

The Second Gate: Controlling Chinese Design Files

In addition to controls on the exports of controlled chips, BIS revised existing controls to restrict Chinese chip design firms from sending their advanced chip-design files to international foundries, including TSMC. In October 2022, BIS controlled technology developed by an entity in China or Macau for the production of controlled chips (i.e., chip-design files, also known as GDSII files). The October 17, 2023, restrictions expanded this control to technology developed by any D:5M-headquartered entity.14 This control relies on the Advanced Computing FDPR, meaning that it only applies so long as the D:5M-headquartered entity used U.S.-origin electronic design automation (EDA) software in the design process. A license is required to export these controlled design files from a D:5M-headquartered entity to anywhere in the world. BIS also attempts to address diversion of these design files by requiring an additional license if they are re-exported from Country Groups D:1 or D:4.15

Practically, this is a deterrence measure for foundries. For example, take a Chinese firm that designs a controlled chip and exports the file to TSMC in Taiwan but does not apply for a BIS license to do so. If TSMC receives the file and fabricates the chip, they could inadvertently become part of the Chinese firm’s export control violation. This control encourages foundries like TSMC to ask more questions when they consider taking on a Chinese customer. While foundries conduct due diligence to avoid violations, they lack the technology to screen incoming design files for the TPP and PD criteria, so they primarily rely on their customers to provide accurate information on whether their chip meets the performance criteria. To help foundries detect potential export violations, BIS provided additional due diligence guidance in the latest controls, as discussed below.

New Red Flag to Identify Controlled Chips

The October 17, 2023, rule added a new red flag to help foundries detect export control evasion by chip design firms. To help ensure that the foundry is not illegally making a controlled chip, foundries are required to conduct more due diligence on the inbound design files. If the foundry, based on the design files, identifies that the customer is seeking to produce integrated circuits, a computer, electronic assemblies, or components that will incorporate more than 50 billion transistors and that will have high-bandwidth memory (HBM), the company has a duty to investigate further. Foundries that identify a red flag may ask their customers more questions, meet with their customers, or analyze the products in greater detail. While foundries may resolve their suspicions through this process, firms often go many steps beyond the text of the regulations to ensure they “know” they are not committing a violation.16

With the addition of this new red flag, BIS has likely made it significantly more difficult for Chinese design firms to circumvent U.S. export controls.

Conclusion

The Biden administration believes that the fast-evolving AI landscape will necessitate annual regulation updates in order to achieve its objectives. One of the key issues that will likely be addressed in the coming year is restrictions on cloud service providers (CSPs) providing remote access to advanced node semiconductors to Chinese customers. While the latest controls addressed part of the issue by preventing companies headquartered in U.S.-arms-embargoed countries, including China, from purchasing advanced-node semiconductors for their subsidiary datacenters abroad, Chinese companies and their foreign subsidiaries will still be able to rent access to advanced chips via CSPs headquartered in non-U.S.-arms-embargoed countries, including U.S. CSPs.

In the meantime, we expect that, at least in the short term, these controls will force Chinese companies to rely on their stockpiles of previously imported chips and less-advanced chips. Furthermore, Chinese CSPs—including Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent—will be at a competitive disadvantage when competing with U.S. CSPs—such as Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform—in the global cloud market. Chinese companies will likely feel an increased pressure to indigenize and find domestic alternatives to restricted items and technologies. But ultimately, how these effects will translate to slowing China’s ability to use large-scale AI models to develop WMDs and advanced conventional weapons or pursue broader military modernization goals is an open question.

- BIS also updated controls on supercomputing items and semiconductor manufacturing equipment which we will address in a forthcoming blog post. ↩︎

- TPP is extremely similar to the original performance metric defined in the October 7, 2022, controls. BIS’s re-definition of the term primarily provides additional detail to assist with compliance. To calculate TPP, calculate a chip’s performance (on dense matrices) for integer operations (e.g., INT8 TOPS) and floating point operations (e.g., FP16 FLOPS) for all possible bit lengths, then choose the highest value. A chip’s TPP may change between when it leaves the fab as a die on a wafer and when it leaves the packaging facility as a finished chip. For a chip package that contains multiple dies, the TPP of each die will be lower than the TPP of the whole chip. However, for a package containing just one die, the unpackaged die’s TPP may be higher than the TPP of the final package, because a chip’s performance is often cut down during the test and packaging process. ↩︎

- To calculate PD, divide TPP by the area (measured in square millimeters) of all logic dies on the chip manufactured with a process node that uses a non-planar transistor architecture (i.e., typically 16nm or below). In a November 6, 2023, briefing, Assistant Secretary of Commerce Thea D. Rozman Kendler clarified that:

1. The entire area of (non-planar) logic dies should be counted—including caches, and

2. Separate memory stacks (e.g., high-bandwidth memory packaged with the logic chip) should be excluded from the area calculation. ↩︎ - This is the case because TPP and PD should be calculated for each “integrated circuit,” and integrated circuits have a very broad definition in the Export Administration Regulations, including multiple semiconductor packages bonded to a common printed circuit board substrate. ↩︎

- “Expedited license” refers to exports and reexports to Country Group D:5 (U.S.-arms-embargoed countries) and Macau, which require an application to BIS at least 25 calendar days prior to shipment. ↩︎

- Datacenter chips require a regular license if they have: 1) a TPP of 4800 or more; or 2) a TPP 1600 or more and a PD of 5.92 or more. BIS classifies these chips as Export Control Classification Number (ECCN) 3A090.a.1 and 3A090.a.2, respectively. ↩︎

- Datacenter chips are NAC-eligible if they have: 1) a TPP between 2400 and 4800 and a PD between 1.6 and 5.92; or 2) a TPP of 1600 or more and a PD between 3.2 and 5.92. BIS classifies these chips as ECCN 3A090.b.1 and 3A090.b.2, respectively. ↩︎

- An export license may still be required if other parts of the EAR (e.g., Entity List) apply. ↩︎

- Non-datacenter chips are NAC-eligible if they have a TPP of 4800 or more. ↩︎

- The rule excludes countries that are also listed in A:5 or A:6. Israel is listed in Country Groups D:4 and A:6. Cyprus is listed in Country Groups D:5 and A:6. ↩︎

- An entity headquartered in (or whose ultimate parent is headquartered in) a U.S.-arms-embargoed country (D:5) or Macau. ↩︎

- An entity headquartered in (or whose ultimate parent is headquartered in) a U.S.-arms-embargoed country (D:5) or Macau. ↩︎

- “D:5M” and “D:1 or D:4” in the “Country” column excludes A:5 and A:6 (Israel and Cyprus); “non-D:1, D:4, D:5 country” includes A:5 and A:6 (Israel and Cyprus); “D:5M-HQ’d entity” in the “Entity Type” column is used here as shorthand for entities headquartered in (or whose ultimate parent is headquartered in) a U.S.-arms-embargoed country (D:5) or Macau. ↩︎

- An entity headquartered in (or whose ultimate parent is headquartered in) a U.S.-arms-embargoed country (D:5) or Macau. ↩︎

- Excludes A:5 and A:6 (Israel and Cyprus). ↩︎

- Firms are liable when they “have knowledge” of an export control violation. This even includes knowing that a violation is likely to occur in the future. Furthermore, if an individual employee of a firm “has knowledge” of a violation, it is assumed that the firm as a whole has knowledge and is therefore liable. ↩︎